I have written several times about the fact that measuring our progress in the current recession (and beyond) requires several measures, not just one. Too often I pick up the paper and someone is talking all about one measure that is the key. One day it’s unemployment, another day it’s bank debt risk, and the next day it’s something else. While my opinion on that hasn’t changed, Eric Zencey’s article G.D.P. R.I.P. in the paper yesterday really surprised me, because a measure that we are all familiar with, that we all understand, doesn’t really mean what it has come to imply.

in the paper yesterday really surprised me, because a measure that we are all familiar with, that we all understand, doesn’t really mean what it has come to imply.

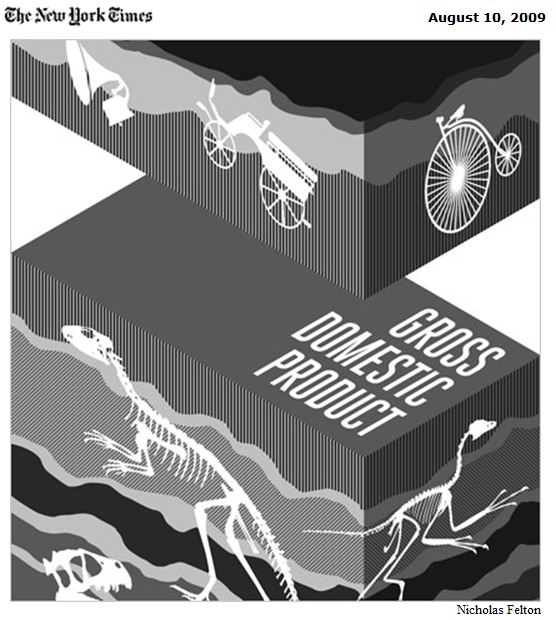

Gross Domestic Product has come to be synonymous with how well a country is doing, and I think that has gone largely unquestioned for a long time. So when Zencey explains with compelling example after compelling example that it means something different, I agreed with him that we need a new label for this measure. The basic argument is that G.D.P. literally only tracks the value of the transactions that take place. As he puts, it when hurricane Katrina hit, it resulted in an $82B increase in the G.D.P., but by no means were we better off. Someone can dry their laundry in the sun, and they are (in a very simple sense) better off, but there is no transaction captured in the G.D.P., and I can write a check for $50,000 today, which would seem good for the G.D.P., but that would send me into debt, and I would absolutely not be better off.

Thankfully, Zencey is realistic enough to know that we aren’t going to throw away the statistic known as the G.D.P., but I think he’s right in waking us all up to the fact that it is a simple transactional measure, not a measure of well being. If we want to measure how well we are doing, as well as the value of things that aren’t on balance sheets (like the bayous he talks about that used to protect New Orleans that were also a gulf shrimp breeding ground – very valuable, were destroyed so they could be developed which look great in the G.D.P. but arguably destroyed more value than they created) we need to look for something more.

How do we do that? That’s a great question. The micro example of drying your clothes in the sun is a hard one, but the example of the bayous and hurricane Katrina is pretty clear, G.D.P. is basically just a part of a larger balance sheet, it’s the simple transactional bit, and there are a couple of other pieces (the bayous were adding value without transactions, so there should have been a replacement cost associated with things like that), and in the case of hurricane Katrina, it seems you almost need a waste measure, that is how much value is thrown away or destroyed (which is probably something the insurance companies can sort out). Good food for thought.

-Ric

Leave a Reply