The central idea of the Rethink book is the ‘how’ trap, that people get so caught up in ‘how” they do something that sometimes a really simple alternative is just impossible for them to see. The ‘why are we going this way’ conversation in driving to a favorite destination ((it rarely matters which route you take, ‘how” you get there as long as “what” you are doing, getting to the restaurant on time, is accomplished) is a good example of this totally human condition that spills into so many areas of our work and personal lives. Generally people aren’t in these ‘how” traps because of stupidity or ill will, it’s simply that they have gotten so used to their ways, or so close to it, they don’t stop and ask “why can’t we do it some other way?”

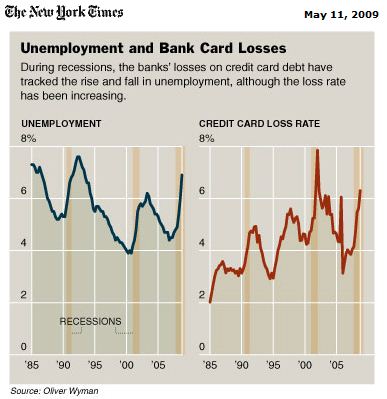

So when I saw this article in the paper today paper today, talking about the risk of $186 billion in credit card losses among banks because of increased unemployment and the fact that credit card loss rate, which used to correlate to unemployment rates, is now growing faster than unemployment, I started to scratch my head and think banks are in a big “how” trap in looking at this debt.

After realizing just how numb I have become to banking numbers these days, thinking that $186 billion is just a fraction of the $800 billion that has been set aside for banks already, the part that left me scratching my head is why they are even talking about card losses right now? Why rush to write off the debt?

I know lots of people who went to college and graduate school that received financial aid to pay the tuition, and from time to time I will hear someone say that they are still paying off their college or medical school, or law school loans. I am 43, and most of these people are around my age, which means some of these debts were incurred over 20 years ago. I know several of my friends have gone for long periods of time without work, and they have simply worked it out with their schools to pay off the debt when they can.

Credit card debt is like school debt in that it already happened. It’s not like it’s an asset like a house or a car that is appreciating or depreciating, or that occupies some land or something like that, it’s just a debt that has some sort of interest rate and payment terms hooked to it. So why do the credit card companies not just work with the card holders and work it out with people like schools do for education debt. If they change “how” they go about managing the debt, yes, it will take them longer to get the $186 billion, but they still should get most of it. Most of these people will get jobs again and they should have to pay for the food, clothing, restaurant bills, gasoline, and running shoes, and so on that make up that credit card debt.

Please, rethink managing credit card debt, so taxpayers don’t have to pick up this tab.

-Ric

Well, it is much cheaper for these FIs to package up their low-performing assets (eg, non-paying credit card accounts) and sell them off en-masse. This is done generally to a debt collection agency, which does exactly as you propose – harasses the debtor until they pay up, or works out a longer-term payment plan (which they can then resell again). The nice gift our government has been giving FIs is that they no longer need to take $0.30 on the dollar (by selling these bad assets to people who can better monetize them). Instead, the gov’t has essentially been paying them $1.00 on the dollar for bad assets (oh, the pain!) There is plenty of game theory involved for the FIs, particularly if they can make the assets look sufficiently toxic (ie, big enough to bring down the FI), the gov’t will step in and buy/guarantee these assets for a lot more than the FIs could sell them through their regular secondary channels. Maybe we need to rethink the US business rules. I think solutions can be found through regulation (although certainly insufficiently), or enforcement & oversight on corporate governance. Executives committing massive fraud are routinely getting awarded for it – when they should be jailed instead. Capitalism is a great solution, but just like every other powerful tool, it needs to be controlled or it simply runs amok.

One of the things to keep in mind when analyzing a problem is to analyze the bigger context for “unintended consequences”. If this context is “Fix Credit Card Debt” then paying it off with Federal money is a very short sighted solution [an example of local optimization]. The banks problem is that it needs to lend money to make a profit. In order to lend money it has to maintain a ratio of assets to debt [a government policy]. This debt that is tied up is hurting the banks ability to lend money. If the government wants to help, it can change the mix in the ratios that banks need to maintain [a government policy] and suspend interest on long term debt [a government mandate] for people that are out of work.

There is no debt being paid off in the bailout scenario. The debt is being transferred from the bank to the government and therefore to their tax paying constituents. Tax paying constituents are the ones that make enough money they pay taxes and therefore have the most consumer spending impact. If you work your way out of the “Fix Credit Card Debt” context, you can analyze it in the bigger problem of “Improve the Economy”. This brings “Increase Consumer Spending” and “Keep Banks Solvent” into the context. It turns out that creating another $186 billion of unsecured debt for the Federal Government may not be in the best interest of either of these problems.

There is some interesting analysis to do to review the consequences of these actions – but there are lots of alternatives that will keep the banking system from failing that don’t require a further increase of federal debt or additional redistribution of income.