Someone recently suggested that my work ignores quantitative analysis and relies solely on qualitative research, and that’s a mis-reading of the approach in the Rethink book. I LOVE getting quantitative, but I have found two risks in starting there.

1) People will attach metrics and quantitative analysis to a block of work without any real knowledge or insight into the role of that work in the performance of the whole (which puts them at high risk of having the wrong measure)

2) Organizations simply look to industry benchmarks as their guide for quantitative analysis, which presumes the work is a commodity function that can just be compared to any other company in their industry.

I am not going to tell you that I am an expert in all industries, but manufacturing is one of the only industries I am aware of where you can just take industry benchmarks and apply them almost across the board to jump into the world of quantitative analysis, which is why the Six Sigma method is so fantastic for manufacturing companies. For those not familiar with Six Sigma, in the simplest terms it eliminates variance in the performance of a specific piece of work. And to be sure there are parts of every organization where elimination of variance is a very helpful thing, but in my experience, in most other industries, starting with the assumption that you need to eliminate variance without first understanding the role of the work in the overall, is at least risky, and at worst potentially counterproductive.

I often compare the operating models of Costco and Sam’s Club. Two companies in the same basic retail industry, and “what” they do is nearly identical, where “how” they do certain things is radically different because their brand and identity are different. Sam’s Club cares a lot about whose products are on their shelves, and they work very hard to negotiate deals with those big name product companies so they can make enough profit when they sell them at great prices. Costco by contrast doesn’t care whose products are on their shelves, and they don’t make any money selling their products (by choice), they make their profits primarily from the membership dues that are required to be a member to shop there. Because membership renewal is so key to them, they give away free food around most corners, the stores are well lighted, employees are very friendly. So if I were to start with a quantitative approach and drive for standard retail industry metrics at Costco without first understanding what they value, I would literally destroy value.

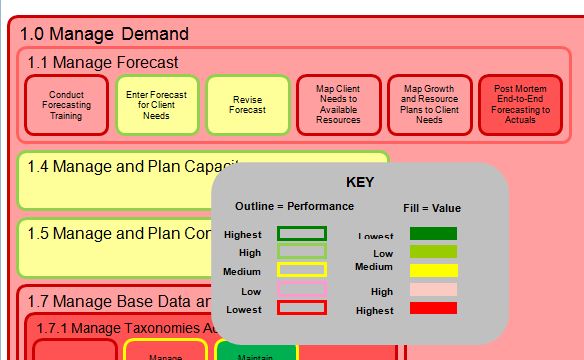

So because most organizations are not as explicit as Costco about what they value at a high level, let alone at a more granular level, and because the risks are high that they already have the wrong metrics on a piece of work, I start with the heat maps that I do around value and performance to listen to what people think is most valuable (which I define in the book Rethink) and how they think it’s currently performing. My heat maps always start with two colors per block of work, an outline or border color and an interior color (see the Key bel0w). With these diagrams, we can be more explicit about where the high value and low value work is, and from there we start to get more quantitative and ask, what is the right metric, and which block or blocks of work will get us there, and once we have made those assertions, then we can get into the discussion of “how” we do it in terms of process re-engineerging, or Six Sigma, or Lean, or Agile, or some other method.

So yes I love the quantitative side, but it’s dangerous to start there unless you are sure that you are working with a commodity function that allows you to safely jump in with industry benchmarks.

-Ric

While your biggest contribution is to stir the thinker to re-think the process organization based on the “how” we still need some quantitative weight to also stir the higher priority process based on its cost – That is if we can superimpose on the “Heat Map” a relative process cost with respect to the total cost, I am sure the heat map will change color based on relativity. You can start with a raw heat map without cost relativity then a follow up map showing the relative individual process cost to the total cost… Some ABC (Actitvity Base Costing) concepts can be applied here… It can be an additional (absolute or percent) cost label onto the heat map – if changing color is not desirable…

I couldn’t agree more.

One of the challenges with mapping cost to process is that process maps tend not to be schematized, in the sense that their start/stop points and some of their attributes vary based on subjective viewpoints. While that turns out to be a very good thing when it comes time to map processes, the risk is in trying to tie an objective cost amount, to a subjective, often fluid viewpoint. Starting with the “what” view, which has proven to be highly durable and schematized, you can link to objective stable pieces of information. From there attaching the “how” layers of people, process, and technology (among others) empowers you to really test what are, and are not, the true causes of performance.

-Ric

Hi, good post. I have been thinking about this topic,so thanks for posting. I’ll certainly be coming back to your posts.

The best information i have found exactly here. Keep going Thank you